Norton was probably created by Anglo-Saxons in the 6th -7th C. Norton is believed to be derived from North Tun, Tun being Anglo-Saxon for settlement. In the Domesday Book of 1086, Nortone was recorded to have 6 ploughlands. The great historian William Burton referred to a letter he had found which stated: “I was looking for antiquities around this church when I found in a corner an old piece of a pair of organs and upon the end of every key was a carving of a boar.” It seemed a remarkable coincidence that at this period the village had changed its name to Hoggs (Hogges) Norton.

Article by Arthur Tomlin on 7th January 1993 Norton was probably created by Anglo-Saxons in the 6th -7th C. Norton is believed to be derived from North Tun, Tun being Anglo-Saxon for settlement.

The Saxon king Eldred granted Norton a Royal Charter in 951. At that time it was known as Northton.

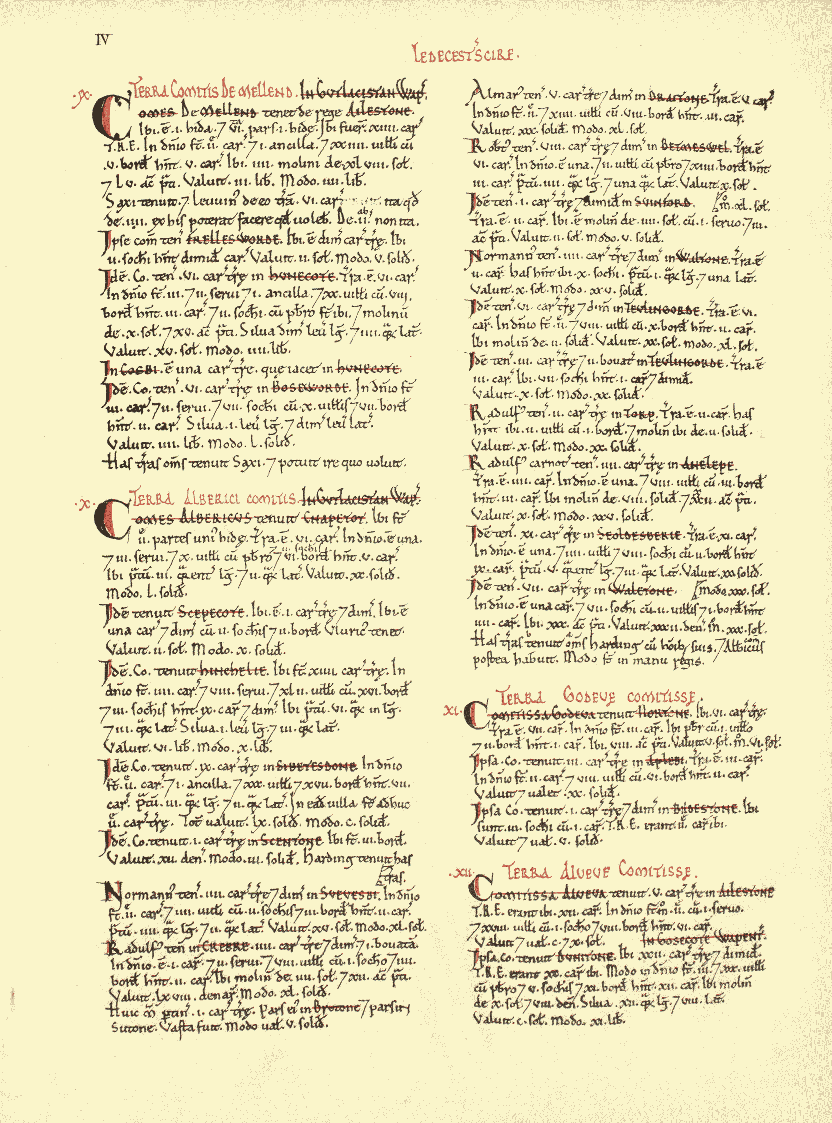

In the Domesday Book of 1086, Nortone was recorded to have 6 ploughlands and was held by Countess Godiva, the wife of Earl Leofric of Mercia.

In 1280, Norton, Snarestone, Appleby and Shackerstone answered collectively as one village. At this period the Ferrers family of Groby held a third share of the village.

Several people in Norton were arrested by the Sheriff in 1325 for the murder of William de Monte Gomeri, which took place on a heath near the Abbey of Merevale. It was said that he was struck on the head with a sword and died in his wife’s arms.

It is pre-recorded that in 1326 the Abbess of Polesworth was allowed to appropriate to herself two shillings and one penny as annual rent together with the appurtenances at Norton.

In 1564, there were 16 families living in the village and when the Hearth Tax came into force in 1664 the returns showed that 40 inhabitants in Norton paid tax.

{gallery}norton-history,single=William Burton_large.jpg,salign=left,connect=sige{/gallery}

The great 17th century Leicestershire antiquarian William Burton referred to a letter he had found which stated: “I was looking for antiquities around this church when I found in a corner an old piece of a pair of organs and upon the end of every key was a carving of a boar.” It seemed a remarkable coincidence that at this period the village had changed its name to Hoggs (Hogges) Norton.

The Moore family had a long association with Norton and Appleby.

Charles Moore of Norton purchased the manor at Appleby in 1599.

His second son, John, raised a fortune as a merchant in London in the East India trade.

In 1681, he became Lord Mayor of London and was elected President of Christ’s Hospital in the same year. During his term of office he was knighted by Charles II for his loyal services. This great man who was born and baptised in Norton was a great philanthropist and devoted much of his fortune to the less fortunate.

Sir John founded the school at Appleby Parva which was designed by Wren, and catered for 50 boy boarders who came from all over the country until 1706. Originally it was restricted to boys from Norton, Appleby and neighbouring villages. The figure of the founder in his official robes stands in an arch in the wall. The school closed in 1904 due to lack of support but was reopened in 1959 by Sir Robert Martin.

http://www.sirjohnmoore.org.uk/index.php/heritage-centre-and-community-gallery

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Moore_(Lord_Mayor)

Sir John died without a successor in 1702, aged 82 years.

A villager called Frederick Bowen kept a series of diaries from 1881 until 1920. He was a farm labourer and miller.

He recalled that in 1881 many people were buried by snow and a number froze to death. In Atherstone hailstones fell and the town was flooded, and many went home for dinner in boats.

On 4th April 1889, the Prince of Wales came to Gopsall and later attended Leicester races. In 1891 Queen Victoria passed through Snarestone on her way to Derby to lay a stone at the infirmary.

His first diary stated that the railway from Nuneaton to Ashby had opened in 1873 and the first load of Indian corn was unloaded at Snarestone station.

He recalled Lord Curzon’s coming of age when 900 bottles of champagne were consumed, and finally in 1919 Earl Howe’s estate at Gotham in Nottinghamshire and Gopsall were sold and the flag pole at the hall came down forever. The last entry in his diary came in 1920 and said, “hand will not write.” He died in 1922 aged 75 years.

Present day Norton residents might be interested to discover that in the early 1700s Norton had a ‘shop’ or general store owned by an Appleby farmer, which stocked a great range of useful goods.

Norton shop

James How, who is appears from his probate inventory to have been a farmer with lands in Appleby’s open fields, had two shops, one in Appleby and one in Norton. After his death, on 17th July, 1721, John White and Joseph Drath, the Appleby appraisers, drew up an inventory of his goods for probate, including a valuation of the stock in both shops. The Appleby shop with its attached ‘working shop and chamber over’ was the larger, valued at £66 while the shop in Norton had stock worth only about £20.

Like the shop in Appleby, the Norton shop had a range of useful products such as flax and hemp, wood, pitch and oil, soaps and starches.

There was also a stock of tobacco packed in boxes, with an estimated value of 10s. This represents about ten pounds of ordinary tobacco at an estimated value of a shilling a pound – a modest amount compared to the Appleby shop which stocked twenty eight pounds of best tobacco and sixty three pounds of ordinary altogether worth £4.15.8

For the women of the parish, or perhaps to meet the needs of local clothiers, he stocked mohair, silks and thread, inkle, laces and buttons. (Inkle refers to the linen thread or yarn which was woven into belts and tapes on an Inkleloom). The Norton shop also stocked foodstuffs such as raisins and currants, malt (good and bad), and sugar.

Seeds and nails were probably kept in boxes and bins and weighed out by the pound – hence the inclusion in the inventory of seven brass weights and a set of scales. James’ business appears to have been quite profitable, despite his book debts ‘good and bad’ amounting to £19.0.2 – the amount extended on credit. A full transcript of James’ inventory can be found on the Appleby website.

The Norton Census provides a very detailed description of the village in 1881.

Altogether the census lists a population of 395 inhabitants scattered over 87 households, including Gopsall Hall and its attached farm cottages. The village had eight “private houses” (including the Hall), 72 “cottages”, two shops, a pub and ten uninhabited houses. There was also the Rectory alongside Holy Trinity Church and the Primitive Methodist chapel. Although most of the householder heads gave their birthplace as either in Norton or Bilston, about a third were outsiders, mainly from adjacent parishes.

The Rectory was occupied by a curate, Alfred Allen from Lambeth in Surrey and his wife Harriet, and they employed two live-in domestic servants.

Gopsall Hall was occupied by servants, all fairly young, unmarried women who describe themselves as “domestic housekeepers” or “laundry maids”, the head housekeeper being listed as Jane Williams, born in Wales. Attached to the hall was a Gamekeeper’s cottage, the Gardener’s house, Garden Sheds and Stables. The Gamekeeper’s cottage was occupied by the head gamekeeper, William Peach, and his son, who is also described as a gamekeeper. Robert Williams “employing 11 men”, was the head gardener in the Gardener’s House. Four young men lived in the Garden Sheds. Frederick Collen, the head coachman with two Grooms occupied Gopsall Stables.

The principal landholders, those who could probably be described as gentlemen farmers or yeoman, typically described their dwellings as “Private Houses”. The largest holding was in possession of Thomas Ratcliff, originally from Worthington, who farmed 527 acres and employed eight men and four boys. He had five servants including Selina Kingsey, employed as a cook, Fanny Ridway his housemaid, Thomas Holt, the Groom and William Twigg, who is described as a “Cow Boy”.

His neighbour, John Ratcliff, was very likely related to Thomas Ratcliff. He farmed 270 acres, employing four men and seven boys. One of his servants Annie Amies describes herself as a “governess”.

Samuel Foster with 330 acres employed five men and a boy, three of them “indoor farm servants”.

James Arnold, born in Market Bosworth, farmed 400 acres and employed ten people, and had two domestic servants and a farm servant living in. Both of his two young daughters are described as “scholars”.

Emilia Barber, 62 years old and originally from Appleby, farmed 120 acres and employed two boys

The Smallholders included John Dean, farming 16 acres who had a young family and a daughter employed as a dressmaker, and George Marshall, farming 30 acres. One of George’s sons was an apprentice blacksmith, the rest were “scholars”.

James Stretton who gave his occupation as a Miller as well as Farmer, was married with four children. He farmed 16 acres and employed one man and the family kept a 16 year old girl as a domestic servant.

Richard Pegg, originally from Orton on the Hill, farmed 54 acres and had four sons. There were other Peggs in the parish, including Charles Pegg aged 65, who describes himself as an “agricultural labourer” yet lists among his household three servants including an Irish “Under butler”, a scullery maid and a domestic “Baker and Brewer”. Presumably Charles Pegg was a retired farmer.

Farm labourers were the most numerous occupation, accounting for the occupants of about fifty three households. Most farm labourers probably lived in tied cottages, including Richard Hestell, Thomas Larkin, Edward Harris, John Rowel and his son William, William Smalley, James Hodgkinson, John Wain, Samuel Barwell, John Gilbert, William Jackson (one of his son’s William giving his occupation as a “Groom”), George Summers, Thomas Hancote, William Smith, Thomas Cope, William Booton, John Harrison, Thomas Bradford, William Harding, and George Miller.

Frederick Miller, a farm labourer living in a cottage next door to George, describes himself as a “visitor”, and was probably a visiting relative.

James Miller, Thomas Wilton, Thomas Cope, John Brown, Thomas Harding (his son, Samuel, a “farmer’s boy”), Joseph Wardle, James Bown and his son James, George Satchwell (whose son describes himself as a shoemaker)

William Pegg, Samuel Spare, William Brown, of Ratcliffe Barn cottage

Joseph Holt, his daughter a domestic servant, his 10 year old son, Daniel, who was “deaf and dumb”, described as a “farmers boy”.

Samuel Pegg, John Miller, Richard Hambling, Frederick Bown, Thomas Newmans, William Walton, Edward Taylor, William Harrison, George Smith, Joseph Wilkins, James Bown, Henry Spare, Joseph Harrison, all gave their occupations as “farm labourers”.

The Farm Cottages, next to the Hall were also occupied by labourers including, William Twigg and Sam Sentence at Farm Lodge and James Starkey who describes himself as a shepherd.

The gardeners at Gopsall Hall could also be described as farm labourers.

Law and Order was represented by Thomas Achurch, a police constable, who originally came from Great Glen, He had a wife and seven children, all scholars. Also Charles Hammersley, formerly a police sergeant whose daughter Elizabeth Fisher, living at the same address describes herself as a police constable’s wife

The Medical Profession represented by Samuel Bown, a vetinary surgeon

Widows and Single women householders were comparatively rare.

However, there were some women heads of households, including Ann Ottey, who describes herself as a “housekeeper”. Her sister Mary and her son George living with her are both described as “imbeciles”.

Sarah Croshaw also describes herself as a housekeeper, her son is identified as a “letter carrier”.

Shopkeepers included Robert Pegg, whose wife was evidently the village schoolmistress. The Pegg’s probably ran the village’s only general store.

John Marshall describes himself as both as a Blacksmith and the village Innkeeper, one of his sons was an apprentice smithy

Tradesmen include William Davis, the bricklayer employing two men (his son being described as a bricklayer’s journeyman)

Joseph Ball, was a journeyman blacksmith.

George Cooper and Frank White (79) were both retired blacksmiths (Frank’s son describing himself as a “gardener’s labourer”)

George Yeomans was a saddler. The eldest of his children was a “farmer’s boy”, the other four were scholars, George also had a boarder who describes himself as a shoemaker.

Richard Meakin, was a carpenter, but also the local methodist preacher.

George Starkey, the butcher, came from London

William Smith, describes himself as a “master shoe-maker”. Philip Booton, another householder also identifies himself as a shoemaker.

Sarah Wilkins, Harriett Smith, were both “dressmakers”, Mary Robinson described herself as an “annuitant”, formerly employed as a dressmaker.

Mary Magear (78) was also an annuitant, though no occupation is given.

John Goddard described himself as a “Master Tailor”, one of his son’s was a journeyman tailor, and the other an apprentice tailor.

Thomas Wilkins describes himself as a carrier.

Edwin Bowman, born in Appleby, describes himself as a “cattle dealer”.

Source: 1881 British Census, P.R.O. Ref. RG11-3134 [on CD Rom]

© Alan Roberts, April, 2004

https://opendomesday.org/place/SK3207/norton-juxta-twycross/

Norton [-juxta-Twycross] was a settlement in Domesday Book, in the hundred of Guthlaxton and the county of Leicestershire.

It had a recorded population of 4 households in 1086, putting it in the smallest 20% of settlements recorded in Domesday.

View on page: Leicestershire folio 4 »

The church, which is dedicated to the Holy Trinity, was built in the 12th Century. It may originally have been a wooden structure as most churches were around that period.

Norton Holy Trinity Church Gallery

English Heritage listing for Holy Trinity Church

Holy Trinity Harvest Festival – September 2008

The first rector was inducted in 1220 when the village was under the patronage of the Prior of Belvoir.

The west tower was built in the 14th century and has battlements. It originally had a short spire that was taken down in 1890 when it had become unsafe.

In the belfry the windows are all of single light and in a niche in the west wall of the tower is a carved figure sitting like a weary guardian.

In the tower are three bells the oldest being cast in 1640 and the other two in 1663. One bell, which is inscribed “Glory be to God on high”, was recast in 1849 by Taylors of Scarborough at a cost of £24.

The beautiful stained glass east window was made by Warrington in 1841.

Norton can claim to be one of the very few churches in the country to have two pulpits. The smaller one is two tiered and was originally used for reading the lessons whilst the preacher occupied the main pulpit. The lectern was given to the church in 1918 in memory of the Rev William Callahan who was rector of Norton in 1916-17.

The church is extremely fortunate to have a magnificent rare barrel organ in working order. It was painstakingly restored, by John Burns of Nuneaton, In 1980. It was built in London in 1819 by James Butler, an apprentice to the celebrated organ builder George England and installed in Norton in 1840. It was mainly due to the untiring efforts of three lady members of the church that the organ was restored to its former glory. It has three barrels each having 10 tunes including “O God our help in ages past”, One of the most famous families of clock makers in the country came from Barton in the Beans.

An employee of Samuel Deacon came to take the measurements for a turret clock to be installed in Norton church. It was made at Barton and installed in the church on 11th September 1840.

The clock had been almost trouble free for the past 150 years, the measurements have been retained and the cost was £80.

The vestry was built in 1850 at a cost of £100.

In the churchyard is a very unusual gravestone to the memory of John Worthington who died in 1705. The letters all run together with no space between them and many of the letters are back to front. Among the gravestones are two ancient recumbent effigies of a knight and his lady

See also <a href=”index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=31&item=27″ title=”Nichols History of Norton Church”>Nichols History of Norton Church</a></p>

Two early glebe terriers, from 1601 and 1606, provide us with the earliest descriptions of the old Norton parsonage house. Both describe the site of the parsonage with its attached “Homestall” or homestead:

lying between the common street over against the farm house on the east side and the orchard belonging to the … parsonage on the west . And between the church on the north and a backside or close belonging to the parsonage called the overclose on the south, containing an estimate two roods, with a further one rood for the garden and orchard.

lying between the common street over against the farm house on the east side and the orchard belonging to the … parsonage on the west . And between the church on the north and a backside or close belonging to the parsonage called the overclose on the south, containing an estimate two roods, with a further one rood for the garden and orchard

We learn from this brief description that the parsonage house was situated on the corner of the street, directly opposite the church, as further attested by a well-worn path leading from the street to the priest’s door where the parson gained access to church. The parsonage house itself was a fairly substantial building:

six bays built all of tymber and floored over whereof about one baye is covered with tyles and the residue with thatch…disposed into eleven rooms: the hall, two parlours, five chambers, one kitchen, a buttery, a milkhouse (and other outbuildings).

A bay was the term used to measure the size of a building. From common estimates of a “bay” varying from between fifteen to twenty feet width, the parsonage house itself would have been a double-storey building, perhaps a hundred foot long. Various small closes were attached to the homestead. One called the “Dayhouse Close adjacent to the west side of the parsonage Foldyard, occupying three roods, another called the Neather Close on the north side of the churchyard, occupying two roods”. The 1601 terrier also describes a “peece of meadow in Smallthornes Meadow, of three roods and another in Broad Meadow”, clearly indicating that the parson farmed his glebe land.

Two more glebe terriers for 1679 and 1700 describe the parsonage house seemingly little changed from that described in the earlier terriers. The “Houses, Edifices and Buildings” listed as belonging to the parsonage in 1700 still included “the dwelling house with that which adioyneth unto it … comprised of six Bayes of building, four of them plaster fflowers, two boarded with three little pent houses” (provision for extra roof space). Alongside the parsonage, on the north side of the house, was the old Tithe Barn containing three bays of building, with two more barns standing on the east side of the fold yard, one with four little bays and the other, called the “New Barn”, of three bays. At some stage over the course of the seventeenth century two stables and an outhouse of three little bays were built on the south side of the fold yard, and a cow-house was erected on the west side of the new barn.

The old parsonage house of six bays with plaster and boarded floors with its barns and outbuildings was still standing a century later. The glebe terrier drawn up by the rector, Mr Edward Lees, in October, 1790 describes substantially the same structure, including the three little pent houses mentioned in 1679, suggesting that the “rebuilding” of 1725 may have been merely the addition of a brick casing to the original structure.

The 1749 Enclosure Award provides further precise valuations and acreages of the eighteenth-century buildings and glebe lands belonging to the Norton parsonage. We learn from this survey that the rectory house with its adjoining barns, yards and crofts covered four acres and 26 perches, and that the church stood on a croft covering some two acres with additional lands granted in exchange for lands in the Common Fields. The parson had acquired ten acres of Heath Field, “heretofor Commonfields”, part of a flat adjacent to the Heathfield late belonging to Sir Thomas Abney, a 26 acre piece in Snarestone field adjacent to the Appleby hedge, 35 acres in Churchfield along the Snarestone fence, and an 18 acre piece in Woodfield. Altogether, including meadow pieces granted in exchange for pasturage rights, the glebe lands extended over 129 acres and five perches.

With changing tastes and expectations the old parsonage house, a frequent source of contention and claims repairs and maintenance by successive occupants, was eventually abandoned as a rectory. The Rev. W.T. Pearce Mead King, is credited with building the new rectory at the south end of the village in 1850. However, the 1887 ordnance survey map clearly shows the old parsonage house and outbuildings still standing on the site. A lack of any marking as to its ecclesiastical function suggests that it had by that time reverted into a glebe farm.

The new rectory at the southern end of the village lasted until comparatively recent times. Surviving ecclesiastical papers relating to repairs and maintenance in the Leicestershire Record Office provide some quite interesting information about this building. The 1918 submission for the Ecclesiastical Dilapidation Act of 1871, for example, recommends the demolition of a pigsty in the paddock next to the rectory. The Ecclesiastical Insurance Office in 1927 lists in addition to the rectory house, a stable, stalls, a coal shed and a coach house – all signs of increasing amenity and comfort – a thatched cowshed, various implement sheds, a copper house, a loose box and other outbuildings altogether valued against total loss by fire at ₤925. The office also recommends immediate repairs to the tune of ₤90.

Mention can be made here to a list of the incumbents of the new rectory, those following on from those recorded by John Nichols, and compiled from the list of ‘nominations’ drawn up for the archdeaconry court.

There is a fine portrait of the Rev. W.T. Pearce Mead King, the rector who is credited with rebuilding the new parsonage in 1850. However, both the old and the ‘new’ parsonage houses and outbuildings have now disappeared. Little trace of the old rectory opposite the church survives apart from some stone courses in the walls marking the boundaries of the glebe farm.

William Thomas Pearce Mead King, 1850

Thomas Cox, 1869

John Thomas Walker, 1877

Herbert Coke Fowler, 1891

Thomas John Williams-Fisher, 1907

William Callahan, 1916

John Carpenter, 1918

Most of the references to the parsonage are from documents in the Leicestershire Record Office at Wigston. Glebe terriers 1601, 1606 from L.R.O. MF 260; Glebe Terriers, 1679, 1690, 1700, L.R.O. Misc. 1041/2/492-4

Norton Enclosure Award, 1749 Q.S. 47/1/1-2

Norton Tithe Award, 12 Oct 1849 (and map): DE 76/T1/239

Insurance correspondence, 1918: DE 1555/16/1-41

Archdeaconry court nominations, L.R.O. 7D55/692/1-2, &c.

Particular thanks for the advice and assistance of Dr Simon Harratt.

© Alan Roberts, May 2005

The new parsonage house at Norton which the rector, Mr Reuben Clark, finished building in 1725 had fallen into disrepair by the end of the century as the archdeacon, Dr Burnaby records in 1797, ‘The Parsonage House and premises want much repair; which must be done by degrees and as soon as Circumstance allow’ (LRO, 1D/41/18/22 p. 68).

This ‘new’ parsonage house at Norton was the home of at least four 18th century rectors. According to Nichols, Reuben Clarke, who briefly served as rector of Ibstock, was the incumbent at Norton and lived here from 1711 to 1728, followed by Lancelot Jackson (1728-1745). Jackson was succeeded by John Clayton who entered the living on May 31st, 1745 and occupied the parsonage house for almost half a century. He in turn was succeeded by William Carson, M.A. who assumed office on June 27th, 1796, staying until the census in April 1811.

Although by no means a rich living, Norton did attract interest in the fiercely competitive scramble for benefices. The Rev. William Bagshaw Stevens, domestic chaplain at Foremark and headmaster of Repton School sought preferment here, but was put out of the running perhaps by his association with his patron, Sir Francis Burdett, the radical Member of Parliament. In his journal Stevens mentions the living at Norton several times, wondering in one entry, ‘whether such a living would demand Residence’. Later around June 1794, on hearing that Lord Curzon was exerting influence to obtain the living for Tom Gresley, he wondered ‘whether it would be more expedient to wait till some more promising object presents itself’. Finally on hearing that the rectory had become vacant in February, 1796 he notes perhaps with some satisfaction that ‘Gresley was come down from London defeated as to his hopes of Norton’. Even as late as 1st June, 1796 Stevens was still hopeful that ‘the living is not yet given away’, unaware that Carson, a third contender, was destined to have it before the month was up.

Carson may have secured the living but the urgent repairs to the parsonage house which Burnaby recommended in 1797 were still not completed by October 14th, 1829, when it came into the possession of the Hon. Alfred Curzon of Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire. Curzon, who gained preferment through his connections with Earl Howe was a pluralist, the grandfather of the famous statesman, Lord George Nathaniel Curzon. With the option of moving into the living next to Kedleston Hall.

Curzon had no need for the parsonage house in Norton. This might help to explain why references continue to be made about its dilapidated state throughout the nineteenth century. In 1832 it was partly occupied by a curate, ‘the Under Master at Appleby considered as resident here, having apartments in the Rectory House’ (245/50/2 p.155). Again, in 1835 although it is recorded that ‘The Rectory House is in a bad and dangerous state.’ (245/50/6) there is no evidence of any repair work being started.

The incumbents’ replies to lists of questions sent by the commissioners of the so-calledEcclesiastical Revenues Commission provides further evidence about the condition of the Norton, Orton and Twycross parsonages. These replies, supplemented by correspondence relating to the inquiry, give full accounts of the incomes and expenditure of each benefice together with statistical information about the populations of the parishes, providing a revealing insight into the financial problems faced by the poorer local parsons.

At Norton where the Reverend Alfred Curzon is listed as the incumbent from 14th October 1829, the return records a population of 301, with another 74 in that part of Bilston attached to Norton. We learn that the curate was paid a stipend of £80. There was one church which could accommodate 160 people and a “Glebe House” (presumably the parsonage house) which is described merely as “tolerable”, shared by the curate and the tenant of the Glebe lands. The gross annual income of the parish is recorded as £332 – 9 –11¼d of which £200 was rental for the land and part of the house let to the tenant.

In 1842 we learn from archdeacon Bonney that the curate at Norton lived in the rectory house which was still ‘in a bad and dangerous state’ (245/50/8 p. 230), with the rector presumably more comfortably ensconced at Weston Lodge in Kedleston. By this time Curzon had been succeeded by the Reverend Andrew Bloxam, a keen Naturalist, who in the 1820s had sailed on botanical expeditions to the South Seas on HMS Blonde (LRO. papers and correspondence, DE 3442). A prolific writer, he was related to the Mathew Holbeche Bloxam who transcribed and reprinted a fascinating collection of reports and letters relating to the Civil War in Warwickshire. They were respectively the fourth and fifth sons of the Reverend Richard Rouse Bloxam, assistant master at Rugby School and Rector of Brinklow in the County of Warwick.

Andrew Bloxam wrote a series of letters relating to the parsonage in his submissions to obtain relief through Queen Anne’s Bounty in the 1840s. The ‘Bounty’ was first established in 1704 to improve the lot of parsons in the very poorest benefices. In 1862 he submitted a Petition to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners which records that until 1839 the only payment to the vicar of Orton on the Hill (of which Twycross was at that time a chapelry) was £17 paid annually by Earl Howe. The QAB inquiry reveals that the Glebe lands at Orton were rented out for £204 -2 – 0. When the parish was enclosed in 1782 land had been assigned to the vicar in lieu of the small tithes (granted in 1344).

Bloxham complained that he had been put to private expense with the separation of the chapelry from the mother parish, all ‘for the benefit of the population of Twycross’. This was a common complaint as the separation of chapelries from their mother parishes without adequate augmentation, often helped to impoverish rural parsons. There is no mention of course in the QAB correspondence of his predecessor, Mr William Paul, the Orton vicar executed at Tyburn as a Jacobite in 1716 (!)

The QAB returns for Orton and Twycross reveal that the parsonage houses here were well maintained, compared to the rectory at Norton. By this time the parish of Orton on the Hill, which included Twycross and Gopsall, had fallen into the possession of the Bishop of Oxford, the incumbent in 1831 being recorded as Mr John James Corey. According to the inquiry Orton had a population of 350, while Twycross contained 319 people. About two thirds of the population could be accommodated in the various churches and chapels. Mr Cory read prayers and sermons at Orton and Twycross in the morning and evenings alternatively on Sundays, Christmas Day and Good Friday. Prayers were also read twice a week during Lent and on Ascension Day. Here there was a Glebe House ‘made fit for the Residence of the Incumbent’ where the parson lived with a gross annual income amounting to £224 -18 – 6 while at Twycross in 1842 the parson is recorded as ‘resident in the Glebe House which is good.’ (245/50/8 p. 234). The author would be particularly interested to hear if any illustrations or photographs survive of these old parsonage houses.

Notes and References

Throsby, John. …Leicestershire Views…Excursions (1790) ‘Rev Mr Ruben Clarke, finished building the parsonage-house this year’ (viz. 1725) in the margin of the register

Church of England Records Centre, St Bermondsey, London

Church Commissioners QAB correspondence: NB 19/164, 19/164 Pt 2. & ‘F’ files, cf. G.F.A. Best, ‘Temporal Pillars QAB, the Ecclesiastical Commissioners’, Journal of the Church of England (1964)

John Nichols IV, Part iii, p. 850

A.P. Moore, (printed extracts), ‘Leicestershire Livings in the Reign of James I’ A.A.S.R.,xix, pp. 174-82

Cf. The last words of the Reverend Mr. William Paul, Vicar of Orton on the Hill, in the County of Leicester; who was executed on the 13th of July, in the year 1716

[by] Paul, William, 1678-1716; Hall, John, 1716.

Georgina Galbraith (ed.), Journal of the Rev. William Bagshaw Stevens (Oxford, 1965), pp. 154, et seq.

Lincoln Record Office (now Lincoln Archives)

REG XXXVIII, 456, REG XXXIX, 619. REG XL, 372.

Leicestershire Record Office (Wigston Magna)

Archdeacon’s Visitations 1D41/18/21 James Bickham, 1775-9.

pp. 1-296, 1D41/18/22 Andrew Burnaby, 1794-7. pp. 1-297; 245/50, parochial visitations made by Archdeacon Bonney, including parochial visitation books.

LRO misc. Bloxam correspondence NRA 6263.

An act for dividing, allotting and inclosing, the open fields meadows pastures commons and commonable places in the parish of Orton on the Hill in the county of Leicester, and the lands … reputed to belong formerly to the Abbey of Merevale / [by] Great Britain. Parliament, 1782

Plan No. 1. Plan of the Gopsall Estate (situate in the Parishes of Snarestone, Swepstone, Norton-juxta-Twycross, Shackerstone, Odstone, Nailstone, Gopsall, Bilstone, Barton-in-the-Beans, Orton-on-the Hill, Twycross, Congerstone, Carlton, Sheepy Magna and Sibson. Plan No. 2. Enlarged Plans of Villages) in the County of Leicestershire, 1927.

Particularly thanks to Dr Simon Harratt for references to the parsonages at Norton, Orton and Twycross, drawn from his intensive research for his dissertation, “A Tory Anglican Hegemony Misrepresented: Clergy Politics and the People in the Diocese of Lincoln c. 1770-1830”, Lancaster University, 1997.

Update on Bloxam name provided by Michael Beare © Alan Roberts, 2005

The village of Norton has always had close associations with Gopsall. Charles Jennens who built Gopsall Hall in 1750 at a cost of more than £100,000, was a great friend of the “Young Pretender” and also a close associate of Handel who is supposed to have written part of the Messiah in the stone temple in Gopsall Park.

Charles Jennens died childless and left his estate to his niece, and it came by marriage to Penn Asheton Curzon whose son was created the First Lord Howe. The Second Lord Howe was MP for South Leicestershire from 1857 to 1870. Earl Howe built the school, the schoolhouse and the alms houses in Norton in 1839 with the majority of the village belonging to the Gopsall Estate.

Englands Lost Country Houses – Gopsall Hall

The King and Queen Visit Gopsall Hall 1902

Humphrey Jennens (pre 1750)

Charles Jennens (circa 1750 – 1773)

Penn Assheton Curzon, Curzon family and Lord Howe (1773 – unknown)

1919 – 1927 Lord Waring.

1927 – 1932 British Monarchy (Gopsall estate only)

1932 – present British Monarchy (Gopsall estate and Hall)

1942 – 1945 the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) made use of the Hall as an experimental radar base during the Secound World War.

By 1952 most of the buildings were demolished. Gopsall Park Farm was built over most of the original site and is not accessible without invitation.

The present-day remains include parts of the walled garden, the electricity generating building, an underground reservoir, the tree-lined avenue, the gatehouse and the temple ruins associated with Handel.

ref: http://www.reference.com/browse/wiki/Gopsall

You can now visit Handel’s Temple,according to Christopher Simmons, who mailed the web site with this information.

No need to arrange a visit with someone to the temple.I believe it is now open all the time. Access is off the Bilstone – Congerstone School road, going up towards Gopsall Hall Farm. There is a small sign on the right to the temple. You have to walk through a field of corn on the cob and then through a wood, about 1/4 mile in total before you get to the temple.

Regards Chris Simmons

Hinckley & Bosworth Borough Council details on Handel’s Temple and Gopsall Hall

Georgina, Countess Howe. was born on 14th May 1860. She died 9th February 1906. The neighbourhood of Gopsall was overspread with sorrow and sadness, on Saturday last, when the news arrived of the decease of the Countess Howe, whose death took place at Curzon House, Mayfair, W., soon after nine o’clock on Friday night, the 9th inst.

True, the news did not come as a surprise to those who had an intimate knowledge of the state of her ladyship’s health, but it was none the less keenly felt when the sad event had actually taken place. It seemed unspeakably sad that a lady in the prime of life, and so prominent at court and in society, should be snatched away by the rude hand of death, when such a vista of usefulness lay open before her.

Two or three years ago her ladyship was afflicted with a paralytic seizure, and though her many friends hoped that she might be restored to vigorous health again, the fears that she might never permanently recover were uppermost, and these fears have now been realised.

The particulars of her illness, the partial recovery, her journey to Egypt, movements in society, and friendship with royalty, have all , been recorded in the society papers, and it is not our intention to attempt to enlarge upon the noble life of this illustrious lady.

Owing to their many engagements in society, the tenantry on the Gopsall estate have not seen so much of Lord and Lady Howe as they have wished to do, but whenever they have come to Gopsall, which by the way was the favourite home of Lady Howe, they always received a cordial welcome.

When the King and Queen were entertained there some two years ago. Lord and Lady Howe became better known to their tenantry in Leicestershire, and when in September last, at the coming of age festivities of their son, Viscount Curzon, the whole countryside were entertained at Gopsall.

Her ladyship became personally known to a very large number of the residents in the district. Previous to that time she had taken a useful part in local charitable objects, had interested herself in church and school work, and was beloved by all who had met her.

Last Wednesday, snow covered the ground and little knots of villagers stood in sorrowful groups along the route leading from the station to the Hall, discussing the inexpressibly sad event which had deprived their esteemed landlord of the partner in all his joys and sorrows.

Blinds in every house in Shackerstone were drawn down, and a muffled peal was tolling out the message that death was amongst them.

Several carriages were waiting in the little station yard, when a special train arrived bearing the body, which had been removed from Curzon House in the morning. Three special saloons had been brought down to Nuneaton station by the express leaving Euston at 1 am, and upon reaching Nuneaton these were attached to a special engine, which arrived at Shackerstone at 1.20pm.

As the coffin was taken from the saloon it was covered with a beautiful pall of white corded silk, which had in the centre a golden cross reaching nearly the full length of the coffin.

Upon this was laid one large chaplet of violets and lilies of the valley, which had been placed upon the coffin by Earl Howe. Borne upon the shoulders of eight bearers the coffin was carried through the station and placed upon a hearse in waiting.

The members of the family who accompanied the coffin were Earl Howe – Duke of Marlborough, Lady Sarah Wilson, Major Gordon Wilson, Mr John Eyre, Hon Frederick Curzon and Dr Lindley Scott. Following the hearse were two carriages containing the mourners, while the servants of the household followed in other conveyances.

Slowly the cortege wended its way through the little village and entered the park by the Shackerstone drive, the coffin being taken in at the front entrance and conveyed to the chapel where a brief service was held. Simultaneously with the service at Congerstone, a memorial service was held in London at St Margaret’s, Westminster.

Every mark of sympathy and respect towards Lord Howe in his sorrow was shown in the neighbourhood of Gopsall. The bells of the churches were tolled, blinds were drawn and most of the inhabitants were in mourning.

Lord Howe desires to express his heartfelt thanks for the sympathy shown with him in his great sorrow and he is much touched at the kind thought shown to him in his great affliction. The newly-built vault in which the remains were laid to rest is built to contain several bodies and the whole of the work was undertaken by the estate bricklayers, under the direction of Mr Bumett, the steward.

On the evening of the funeral a muffled peal was rung, on the bells of the parish church of St Mary, consisting of call changes, whole pull and stand and short touches ofgrandsire triples, as a token of respect to the memory of the late Countess Howe, by the following performers :- W. Humphreys (Treble); S. White, 2; J. Tansey ,3; W. Sharpe, 4; F. Cotton, 5; G. Thompson.6; W. Cooper, 7; T. Buswell and W. Wall, (Tenor).

The Daily Telegraph in a notice of the sad event says:- The earnest and heartfelt sympathy of all his friends will assuredly be expressed to Earl Howe who has suffered an irretrievable loss in the death, after a long and painful illness, of Countess Howe, which took place on February 9th at her residence in Curzon Street, London. A daughter of the late Duchess of Marlborough, Lady Howe. possessed the strength of character, the keen intelligence and the attractive vivacity which has been so long associated with all the members of a truly gifted race, united in no ordinary measure by the strongest ties of family affection.

The fifth of the six daughters of the seventh Duke of Marlborough, Countess Howe has been the second of the sisters to pass away in the prime of life. In August 1904, while she was herself very ill, she leant the news of the death of Lady Tweedmouth and this severe blow proved very prejudicial to her health, which had caused her friends considerable anxiety for some time previous.

Lady Howe enjoyed the intimate friendship of the King and Queen, and entertained their majesties at Curzon House on many occasions. The last time that the King went there dinner was served in a room on the first floor and Lady Howe was wheeled in an invalid chair to the table in order that his majesty might enjoy the society of his hostess.

Sent in by Chris Simmons

John Nichols’ monumental, four-volume History and Antiquities of Leicestershire (building upon an earlier work by William Burton) provides several pages of fascinating information relating to the history of Norton.

Nichols’ transcripts of deeds, awards and taxation records lists many of the principal landholders and their holdings. One deed from the late Tudor period records that Richard Hill, a yeoman, who died in 1590 leaving lands to his son William (aged 17), held a ‘messuage’; called Hill House in Norton. He also owned a garden with a hort-yard (or orchard) adjacent, the Close on the Heath, another close called Bridge Crofts, and two virgates of arable, all held by knights’ service of the queen as of the Honour of Tutbury. Another prominent landholder, Henry Kendall who died in 1592, left a ‘capital messuage’ [or principal homestead], 161 acres of arable, 30 of meadow and 40 of pasture in Norton as well as other lands in Swithland, Swepston, Twycross &c.

In 1630, during the ‘sheriffealty’ of Mr Wollaston in the reign of Charles I, the freeholders are listed as Thomas Croxsall, John Cooper and William Hill. Henry Kendall of Smythsby, co. Derby was lord of the manor in 1632 and there is further mention of him holding lands here in 1647. At the time of the Restoration Charles II included William Whalley of Norton Esq, worth ₤1,000 p.a. in his list of those eligible for the award of the order of the Knights of the Royal Oak, later abandoned to avoid opening up old animosities (!)

As usual in antiquarian works of this sort, the history of the church, its monumental inscriptions and ‘curiosities’ is well covered. The earliest parish register for Norton begins in 1561. Entries include a ‘memorandum’ from 1613 confirming a grant from William Burman the elder of Norton husbandman, and his son to Thomas Everard and William Hill, describing two cottages joined together upon two hades, ‘nigh a cottage wherein Katherine Kinton, widow nowe dwelleth’ with the surrounding grounds, all to be set aside for the poor of Norton. There is a note in the margin of the register recording that the rector, Mr Reuben Clarke, finished building the parsonage house in 1723.

Nichols also provides an incomplete list of the incumbents and the patrons until 1811, recording that the advowson was held by the prior and convent of Belvoir until 1564 when it reverted to the crown.

Ralph de Querendon, resigned 1329

William de Lobenham, subdean of Sarum, 1329

Robert Bytham, resigned 1421

Thomas Farmer, 1564

Thomas Royle, died 1609

Gabriel Rosse, 1609 to 1658

Josiah Whiston, 1661 -1685

Theophilus Brookes, died 1711

Reubens Clarke, 1711 –

Lancelot Jackson, c. 1728 -1745

John Clayton, 1745 -1791

William Casson, 1796 -1811

Acknowledgements to John Nichols’ History and Antiquities of Leicestershire, Vol. 4, Pt. 2. pp 849-852

Alan Roberts, 2004

Norton’s population increased from the 16 or so families listed in 1564 to the 40 inhabitants assessed for the hearth tax in 1664 (an estimated total population of around 200). By the time of the Parliamentary census of 1801, Norton contained 59 families comprised of a total of 283 inhabitants occupying 54 houses – the largest proportion of them engaged in agriculture with a handful in trades and manufacturing. By April, 1811 ‘according to Mr Carson’ (presumably from the census of that year) there were 61 houses with 290 inhabitants.

Acknowledgements to John Nichols’, History and Antiquities of Leicestershire, Vol. 4, Pt. 2. pp 849-852

Alan Roberts, 2004

Nichols provides a brief transcript of Norton’s Enclosure Award from 1749, listing 28 landholders starting with Charles Jennens, the lord of the manor, and John Clayton the rector, who received £129 in lieu of his glebe. The award describes 1,744 acres of which 377 acres of heath, waste and commons were apparently ‘of little or no value’. The list probably includes all of the principal landholders, Henry Vernon, Joshua Croxall, Thomas Ellen, George Moore Esq, William Blower and Isaac Pearson among others. A copy of this document can be seen in the Leicestershire Record Office [DE QS 47/1/1-2] together with the Tithe Award from 1749 [DE 76/DT.1/63] and a Tithe Map from 1844 [DT 1/63]. A later auctioneer’s map of the Appleby Hall Estate, from 1883, shows the Norton glebe lands stretching from the churchyard towards the Appleby parish boundary.

Acknowledgements to John Nichols’, History and Antiquities of Leicestershire, Vol. 4, Pt. 2. pp 849-852

Alan Roberts, 2004

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norton_Juxta_Twycross

The Twycross Zoo house was the rectory to Norton church in 1851.

The zoo is respected as one of the best managed in the country

The village school closed in the 1940s but the Post Office still remained open until only a few years ago.

The village hall was built in 1920 in memory of those in the village who lost their lives in the First World War.

Our new village hall was built in 1994 after years of hard work fundraising by a hard core of villagers

The village once had a windmill and also a pinfold where stray animals were kept until the appropriate fee for their release was paid.

One of the most notable personalities in Norton was George Henton who was a threshing contractor. Three generations of the family had carried on the business. At one period they had five full sets of threshing tackle driven by steam engines. The engines were manned by drivers who, in the summer months, drove Pat Collins’ fairground steam engines and during the winter months operated the threshing engines